When Busby's Babes came to Dalymount: 60 years on from when Shamrock Rovers clashed with the mighty Man United

Sixty years ago this week, Manchester United visited Dublin to play Shamrock Rovers in the first European match involving an Irish team. Daniel McDonnell looks back on a historic game that was dominated by a Dubliner wearing red by speaking to people who were part of the day and their memories of the tragedy that was to follow

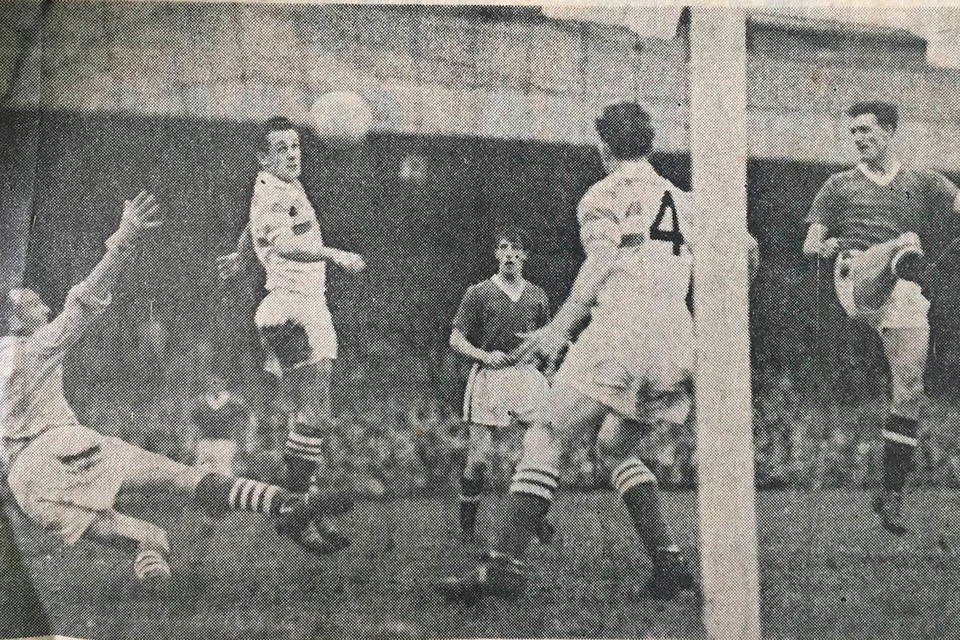

Eamonn D’arcy’s old newspaper cutting of Liam Whelan (right) heading the ball past him for Rovers’ third goal

Eamonn D'Arcy leaps from his chair at his kitchen table. Suddenly, he's 24 and not 84.

He's replaying a moment in his mind, a scene that remains fresh in his thoughts to this day. Dalymount Park on a September evening in 1957. The first European Cup match involving an Irish club and D'arcy is standing between the posts, crouched slightly in his usual position as his Shamrock Rovers side defend a cross that is sent into the penalty area.

Eamonn D’arcy at his home in Naas with the Evening Mail advertisement featuring the teams of Shamrock Rovers and Manchester United ahead of their European Cup game in 1957

There are 46,000 souls crammed into the old stadium watching as a Dubliner rises to meet it, but he is wearing the red of Manchester United, not the green and white hoops of the locals. Liam Whelan is back in his hometown with a point to prove, aware of critics that had been slow to appreciate the greatness of the boy who grew up just down the road.

"I thought he was going to go this way," says D'arcy, acting out a dive to his left side. "I'm there, I'm anticipating it. If I'd waited until he headed the ball it was too late so I had to anticipate what he was going to do. But he saw me going and sent the ball the opposite way."

Later, he climbs the stairs of his house to delve through his treasure chest of pictures and newspaper clippings to find the evidence to support his recollections. The photographer behind the goal captured the scene exactly as he has described. Whelan's goal, his second of the game, gave Manchester United a 3-0 lead and they would double the advantage before full-time to guarantee Matt Busby's Babes comfortable progression into the next round of their second European Cup campaign.

The rest is history. Just not in the way that the protagonists could ever have imagined it.

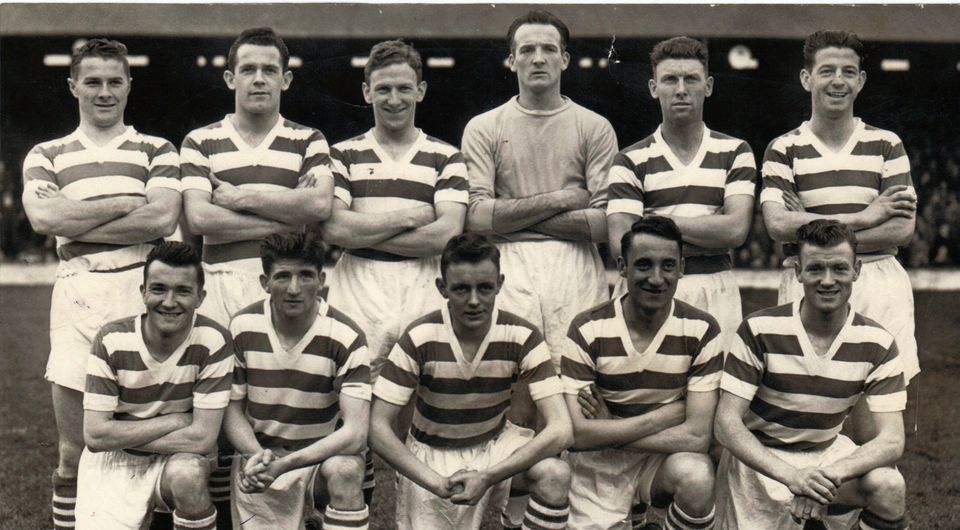

A photograph from the Shamrock Rovers team of the 1957/58 season – Back row, left to right: Liam Hennessy, Gerry Mackey, Ronnie Nolan, Eamonn D’arcy, Paddy Coad, Shay Keogh. Front row, left to right: Jimmy ‘Maxie’ McCann, Noel Peyton, Leo O’Reilly, Tommy Hamilton, Liam Tuohy

***

Two months previously, the draw for the competition had taken place in Paris. Rovers chairman Joe Cunningham Jr represented them at the draw and told the Irish Independent's W P Murphy the story of how it all played out.

"I was sitting next to Matt Busby and we were both wondering what far off places we'd have to visit for it was an open draw in three zones," he said. "Then Sir George Graham of Scotland from UEFA pulled the first name, Shamrock Rovers. That left me gasping and while I was getting my breath back he read out Manchester United.

"Matt Busby looked at me and we beamed at each other for it was just what the doctor ordered for both clubs."

The draw was headline news in Ireland, vying with the other major story of the day which was a report from the Intoxicating Liquor Commission debating the merits of a nationwide 11.30pm closing time.

Liam Whelan in action for Manchester United in 1957 Photo: Getty

The Rovers players were high on the excitement of their news. For player-manager Paddy Coad's Colts, this was an opportunity to test themselves against the best. Hoops forward Tommy Hamilton was thrilled. "The Busby Babes were the team in England and Rovers were the team in Ireland," says Hamilton, who turned 22 in 1957.

For the Bray-born player, the draw had special meaning because he could easily have been with the travelling party. When he was a fifth-year student in Synge Street, United had come calling as part of their expanding project to find the best youngsters in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

He was playing minor GAA for Wicklow as well as excelling on the football field, making occasional weekend trips to England before making the permanent switch.

Hamilton still has a book at his home in Greystones titled 'Sons of United' which details the youth and reserve scene in that period as a special crop broke through. Duncan Edwards and David Pegg were two of the leading lights that were turning heads.

Matt Busby column’s from the ‘Evening Chronicle’ in Manchester warning English readers not to underestimate Rovers on the eve of their game in Dalymount Park

And then there was Whelan, his compatriot, who had played for Home Farm while Hamilton lined out for Johnville. They became great friends, in an Irish gang that included Paddy Kennedy and Northern Irishman Johnny Scott. Hamilton's United dream would end in 1955 because of the realities that hung over footballers post-World War II. Conscription.

United's youngsters were largely able to put it off it for 12 months at a time - conscription was never applied in Northern Ireland so their players escaped - but when Hamilton required a new passport things got complicated.

He was put under pressure to declare himself a British subject under the pre-1949 act and refused. Once his Irish passport came through, it became clear that he wouldn't be able to defer the latest draft so he asked to go home. Busby and the directors agreed once United received 50pc of any future transfer fee.

D'arcy was in England then too and, while he knew Hamilton, Kennedy and Whelan, he watched the other Busby Babes from afar. He'd taken a punt and left Ireland without having a club sorted. A friend gave him the number of his uncle in Sandy Lane in Stretford and he took up a job in the dry-cleaning business.

Remembers

He worked nights and into early morning where he remembers seeing United goalkeeper Ray Wood going by his premises on the way to training. That was the life he craved.

Through Hamilton, he enquired about getting a trial with United and a meeting with Busby was set up. The Scot sat in his car while his right-hand man Jimmy Murphy came out to speak with D'arcy, but it came to nothing when they heard he was still on the books of Dundalk; a release had to be negotiated before they would take a look.

Eventually he wound up in the Third Division with Oldham, where the flamboyant former England captain George Hardwick was player-manager. He gave D'arcy £20 from his own pocket when the triallist explained he didn't have the money to come back the day after he impressed in his audition. Loose ends with Dundalk were sorted by a letter that was penned for him. "They must have got a few quid out of it because they sent me over £50," Darcy quips, "My new deal was £12 a week and £1 a point which was great. I met Stanley Matthews months later and he was only on £14 so on the weeks we won and they didn't know I was on the same money as him."

With no maximum wage, there was little disparity between footballers' wages across the divisions. Nor were they earning much more than the general public; the average weekly pay in the UK rose from £5 to £7 a week across the decade.

United's youngsters collected a £10 signing-on fee when they penned their first contract. But it was their reputation and presence that allowed them to stand out from the crowd.

Manchester was a hub for Irish emigrants in the 1950s and D'arcy and Hamilton both recall the throngs descending on Longford Park in Stretford after Sunday morning mass.

"It was a bit like Marlay Park is now in terms of size," D'arcy explains. The Irish always revealed themselves by tucking their stockings into their boots and running around playing GAA while locals pushing prams or playing bowls went about their normal business.

"But you would see the United players walking through too. They lived in the area and they were like stars," says D'arcy. "I remember Mark Jones walking his dogs, wearing a roundy hat like Mary Poppins. Tommy Taylor too. They'd be going through for their Sunday afternoon stroll. I was thinking 'Posers!'

He recounts another day when a carnival rocked up and one element was a cage where all-comers lined up to take shots at a goalkeeper. D'arcy talked himself into that role, and was blocking shots from all manner of punters until a youngster watching it all unfold stepped forward and asked for a go.

He gave the goalkeeper no chance with three perfect shots. Few recognised the kid with a mop of hair pushed to the side. They would all know who Bobby Charlton was soon enough. D'arcy chuckles at that one.

Charlton was sharing digs with Whelan who was two years older and broke into the senior team first. D'arcy would pay into Old Trafford to watch him and had his own top-flight ambitions but a proposed move to Aston Villa was thwarted by injury.

His plan was to make enough money from that deal to pay for his wedding to the love of his life Alice. But when it collapsed, the pragmatic move was to return to the old sod and mix football commitments with a day job. He managed to impress Coad enough to be signed by Rovers and married Alice in the summer of 1957, although he was sacked from a casual post with the ESB just before he went on honeymoon. Meanwhile, Hamilton had landed on his feet.

"I got into the insurance business which was good to me," he explains. "I was probably better off financially." English football was about the glamour, not the cash, and United were the poster boys.

***

Christy Whelan remains a fountain of knowledge on his brother Liam's life. The affection shines through in his words.

He was a handy player himself, making it to League of Ireland level. So did his youngest brother John, proof that talent ran through the genes. Liam was the star, however, and he was always more of a player than a spectator. The family grew up in the shadow of Dalymount Park and Christy would attend games regularly with his father John who tragically passed away in 1943 when Liam was just eight. The future United star always preferred kicking a ball himself.

"He used to be in the playground in Cabra," continues Christy. "There was a ranger that used to arrange matches for them with all the other playgrounds in Dublin. His team were unbeaten for years. If you go to Dalymount now there's still a section there where if you asked if anyone there had played in the playground with Liam Whelan, a couple of hands would pop up. He used to take Ronnie Whelan Sr, who was our neighbour, on the crossbar of his bike."

Locality

His connection with his locality remained strong, even when he made it big over the water. Homesickness almost prevented him from doing so and Christy recalls his sibling's devastation when Hamilton packed his bags. "They were like brothers over there," he says. Tears were shed.

Whelan stuck it out to prevail and his neighbourhood was proud. "My mother would find it hard to go to church with him," Christy laughs. "She could never get home because people were stopping Liam wanting to talk to him."

The only downside of his United commitments were that they curtailed his international appearances; the FAI rules of the period decreed that any Irishman picked by his club on Saturday could not be selected for international duty the following day. He won just four caps, although one of them came in a starring role at Dalymount in the infamous World Cup qualifier with England in May of 1957 where Irish hearts were broken by John Atyeo's last-minute equaliser. United's Edwards, Pegg, Taylor and Roger Byrne were part of the away side.

Whelan's calling card was the nutmeg and he tormented Edwards in that match. "He nutmegged Duncan who said 'Do that again and you're in for it' so Liam did it again and Duncan thumped him," continues Christy, laughing again. "That was his speciality. He did it to Stanley Matthews at Old Trafford one time. Liam was rolling the ball back and forward and the section of the crowd all knew what was coming. There was a guy near me who stood forward and shouted 'Go on Bill, show him what ball-playing is all about.

"His legs seemed to go forever and he could just pull balls back and control them," enthuses D'arcy, "Now we had Paddy Coad who was a genius, he could have played for Real Madrid. But Coad used his arse more; he'd play with his back to people. Liam was different, he could do this and that (he gets out of his chair again to act out a skiing type motion), he could just swivel around people. He was magic."

There were sceptics in the Irish press, though, with his relatively modest record in the green jersey meaning that he was depicted in certain quarters as a man that still had to prove he was worthy of the hype. "They said he had to prove himself," D'arcy recalls, shaking his head at the absurdity of it all.

***

Dublin buzzed on match-day. Fans had come from around the city and country. Rovers were overwhelmed with telephone and postal applications in the 48 hours after the draw. Tickets were priced at £1 for a seat in the stand, a crown for the reserved terrace and a half-crown (two and six) for open standing.

Christy worked in the Corporation and there was a sweep for the first goalscorer as the employees spoke of nothing else all day. By coincidence, he drew his brother and told him as much; members of the Whelan clan were dotted around the ground.

Kick-off was brought forward to 5.45pm because Dalymount had no floodlights and sunlight was fading. The half-time turnaround was shortened to facilitate a punctual finish.

United paid full respect to their hosts, with Busby flying over on a scouting mission. He had steered his side to the semi-final in the previous season's competition and was wary of an early exit. He had a column with the 'Evening Chronicle' newspaper where he laid out his fears, citing an English League side's struggles against the League of Ireland equivalent a year previously. "The League of Ireland team with SEVEN Shamrock Rovers players gave the England side containing FOUR United players - Byrne, Edwards, Taylor and Violett - the fright of their lives in a game that ended 3-3," said Busby. "Such a form upset could happen again unless United play their very best football."

He praised Rovers' skill and attractive style of play, although added that Coad's team's 'good football' would actually suit United.

Rovers' players had been edgy in the build-up with the competition for places.

"This game was big-time," says D'arcy. "It was fantasy world, but the main thing for us was that we were going to play these fellas and give them a game. Football was different then. They were an attacking team, we were an attacking team. The game was more open."

Hamilton recalls a change of tack recommended by the Cunninghams.

"One thing I've never heard mentioned is that we changed our strip," he says, "The hooped part of the jerseys used to go all the way down under the knicks and the shorts. But in that game we played in a jersey that only had hoops from the chest up to the shoulders.

"It was white from the breast down. Joe Cunningham's theory was that it would make us look bulkier and more muscular. It probably showed you the way we were approaching it. We were coming up against the might of England."

For 30 minutes, Rovers gave as good as they got on a windy evening. But when star centre-forward Taylor broke the deadlock, United were in control.

Whelan bagged his brace after half-time and late goals from Taylor, Johnny Berry and Pegg exposed the difference in fitness levels. In the 2005 book 'We Are Rovers', an oral history of the club, another member of the side Gerry Mackey simply said: "We ran ourselves into the ground. They scored three of their goals when we just couldn't stand up anymore."

Hamilton struggled to make an impression against the imperious Edwards. "He was a great player," he says. "Two great feet, a fantastic build. He could play cross-field passes and he could dribble with the ball too. And remember, he was just 20 going on 21."

For the goalie, it was a particularly tough brief and picking the ball out of the net six times was bad for the spirits. D'arcy's mood was lifted by a consoling word from Coad on the way out of the dressing room, telling him he would definitely be playing in the second leg.

Full time wasn't the end of the formalities, though, with a dinner arranged in the Gresham Hotel for both sides.

United presented the Rovers players with a travel clock, a memento that D'arcy and Hamilton have kept. Hamilton caught up with friends that he remained on good terms with. D'arcy engaged in small talk and was observing.

"The strange thing was, when you saw all these guys in suits, they were just one of us," he explains. "They were normal. Everyone on the pitch would say 'Duncan Edwards, what a huge fella'. When you see him in his regular clothes it was different. It's that illusion of presence that you have on the park.

"We were there for a while, but it was quiet enough. I'd always find with players like that, there's a confidence thing. On the park, they're extroverts. When they come in, they're introverts. There was some chat but not too much as we knew we had to play them again."

The visiting press were complimentary about the Hoops, while seizing upon the obvious angle from the game. "Bill Whelan, the smiling Irishman born just down the road, led this scientific slaughter of Shamrock Rovers' European hopes," wrote Frank Taylor in the 'News Chronicle'. The 'Daily Herald' said it was an act of revenge for Whelan in response to local criticism.

Colourful

Henry Rose, a colourful writer in the 'Daily Express', went down a different route. "Sounds like a walk-over doesn't it?," he kicked off his piece. "Sounds like taking candy from a child doesn't it? Take it from me. It was nothing of the kind. Bravo, Shamrock Rovers. You have nothing to reproach yourself for. Better teams have wilted under this smashing, crashing, soccer dreadnought."

Naturally, there was trepidation about what the return meeting would hold for the Irish side. United had knocked ten past Anderlecht at Old Trafford in the corresponding round 12 months previously. But Rovers knuckled down and performed with credit under the novelty of the floodlights. Hamilton enjoyed the exhilaration of scoring against his old club in a 3-2 defeat and they were applauded off the park.

What D'arcy recalls is the little details. "When we went into the away dressing room, there were coat-hangers which was being treated like royalty, a little simple thing like that," he laughs. "They were telling me afterwards that some team played there and a fella took his with him. His club got an official letter in the post from Manchester United saying player number seven's coat-hanger was missing and they wanted them to send it back."

With pride restored, the Rovers players went back to their daily lives, convinced they'd been swatted aside by a team that was going all the way.

***

In February 1958, D'arcy had taken a new job installing TV aerials. By complete coincidence, he was on Anglesea Road putting one up for his other employers, the Cunninghams, when the devastating news from Munich reached these shores. "It was Mary-Jane Cunningham (Joe's wife) that came out and told me," he says. "She said 'Did you hear the news? United have crashed. The information was coming through very slowly but it was unreal, you couldn't believe it."

Hamilton was in the accounts department of the insurance corporation in Dame Street. "The chief clerk came up to me at around 4pm in the afternoon," he says, his voice quietening. "He said, 'Listen, there's been a terrible crash, the Manchester United players. If you want you can go now."

The compassion was appreciated. He went straight to the Whelan family home where neighbours were streaming in and out. "The radio was on," he continues. "And we were just listening for some news. Eventually it came through that Liam was dead. Everyone knelt down and said the rosary. That shock, I can still feel it now."

Ireland was united in grief with Manchester. The fact that four of the other victims - Byrne (who had an Irish father), Edwards, Taylor and Pegg - had played in Phibsborough just months earlier made it all the more surreal. Jones, Geoff Bent, Eddie Colman and 15 other passengers also perished. D'arcy mentions the press men who provided the clippings that he has kept hold of. Clarke was the only journalist to survive. Rose didn't make it. Former Man City goalkeeper Frank Swift had switched careers to work for the 'News of the World'. D'arcy had the pleasure of sharing a pitch with him once.

Whelan's funeral brought Dublin to a standstill. He was a non-playing member of the Belgrade trip having lost his place in the side to his good friend Charlton, with Christy of the opinion that news that his mother was unwell had affected his form. Regular observers reckoned it was only a temporary blip for a player with his ability. His strike-rate of 52 goals in 96 United appearances was remarkable for an inside forward.

Christy is proud that there's a bridge near his Cabra home named after his brother and was honoured that Charlton, who has stayed in touch with the family, came over for the official opening. There are times, though, when discussions take place about Ireland's greatest ever player and he is aggrieved that the name doesn't come up. That was surely his destiny.

"Bobby himself said in his first book that he wanted to be the most skilful player in the world but as long as Billy Whelan was in the first team he couldn't be," says Christy, "He'd have been brilliant with United. He'd have got plenty of caps for Ireland. But unfortunately the way things worked out, the way things went..."

There will always be a profound sense of loss for what could have been. Hamilton also wonders what his old mate might have gone on to do. He brings up a United youth tour of Switzerland and Germany in 1954 when a delegation from the Brazilian national team wanted to know all about the Irish lad with the silky skills. In the years that followed, he did encounter a couple of the survivors, including a chance meeting with Busby on the way back from honeymoon just over a decade later.

The Scot went on to build a European Cup winning side, but there's a certain mystique about the Babes that will maintain their prominent place in the club's history.

The Rovers squad appreciated the significance of being one of the few overseas sides to face them.

Last year a gathering was arranged in the Red Cow for the surviving members of the '57 team - Coad, Liam Tuohy, Mickey Burke and Paddy Ambrose are no longer with us - and seven managed to make it along; D'arcy, Hamilton, Mackey, Ronnie Nolan, Shay Keogh, Liam Hennessy and Maxie McCann; the latter was dropped for Dalymount but recalled for Old Trafford where he got the other goal. Noel Peyton, who played in both games, settled in the UK after joining Leeds and still lives there.

Contingent

The locally-based contingent have met intermittently over the years; D'arcy and Hamilton remain active golfers, but they're all in the over-80 category now so naturally some are in better health than others. A photo was taken at the reunion but D'arcy prefers pictures of the team in their pomp; that's how he would like them to remembered.

D'arcy - the successor to the revered Christy O'Callaghan, can still reel off their attributes. "They were all great players," he says. "Ronnie Nolan was fantastic, you'd never meet anybody as single-minded as Ronnie. And one of the most under-rated of them all was Noel Peyton who sometimes never gets mentioned. He was brilliant."

D'arcy - who later managed the Irish ladies' side - opens the door into a room next to his kitchen and the walls are covered with memorabilia.

It's not just confined to football; he was one of the drivers during the 2006 Ryder Cup at the K Club and there's a signed Pádraig Harrington hat in a prominent position. But everything else relates to his own career and it's the posterboards from the United game that are the centrepiece.

Perched on the edge of an old advertisement featuring team photos of both sides is a scarf he picked up many years later that bears the names of the crash victims.

"If people don't talk about it, then it's gone," he says, as he walks his guest towards the door after spending a couple of hours immersed in memory lane. It's the first-hand accounts of their greatness that preserve the legacy.

As D'arcy says goodbye, his mind is back in goals, reminiscing about trying to judge where Whelan is going. That's the story he keeps coming back to.

Sixty years may have passed, but there are some memories that will never die.