'A woman I can barely remember but a mother I will never forget' - Shay Given opens up on his mother's death

I'm four years old. A grand-looking woman of just 41, her glossy, jet-black hair falling across her emaciated shoulders, lies in a bed in a Manorhamilton hospital, slap-bang on the N16 in County Leitrim, surrounded by machines beeping, lines feeding, drugs seeping.

There are chewy toffees and drinks on the sideboard, cards littered around the bed, an old newspaper or two frittering around on the spare, hard-worn plastic seats in the ward.

She is Agnes Given. My mum. She is dying of cancer.

This grand-looking woman of 41 loves a drop of brandy, a dance and a chatter with her five sisters and anyone else who will sit with her for as long as her strength will allow. She's not much of a singer, preferring to leave that to others, but she'll drag you up for a dance or two when the time is right. Or, at least she did. Before the back pains started.

Her constant agony has done little to dim her smile and she remains as mentally strong as ever, despite the crippling pain that has overtaken her life.

She knows she will not get out of bed again, won't chase me or any of her other five children, will never get to see them grow up. Her days as a midwife in Strabane are over. In fact, most of her days are nearly over.

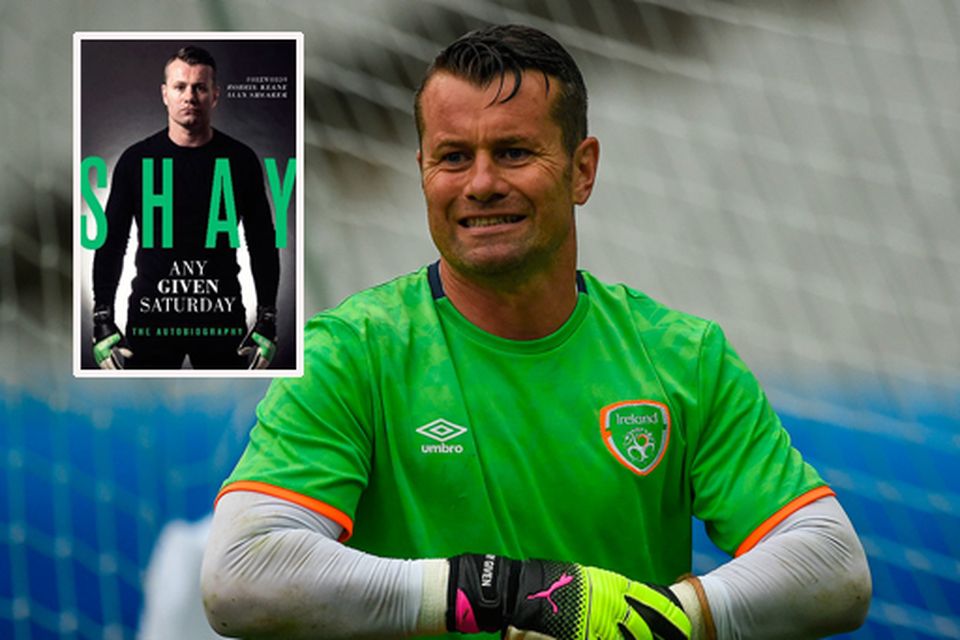

Shay: Any Given Saturday is published by Trinity Mirror Sport Media. It is on sale from this Thursday. Shay will be signing copies of the book on Saturday next at noon in Dublin, at the Eason store on O’Connell St. He will also be in the Eason store in Letterkenny on Sunday at 1pm; Dubray, Shop St Galway on November 11 at 11am; O’Mahony’s Bookshop, O’Connell St, Limerick on November 11 at 3pm; and the Eason store on Donegall Place, Belfast on December 3 at 1.30pm

As she lies patiently, crossing herself and praying to God while awaiting the arrival of my exhausted dad, Seamus, racing up from Lifford in his clapped-out car every night to comfort his darling wife, the tumour that is silently, relentlessly, thrashing away at the base of her spine grows by the hour.

A shabby sideroom at the hospital, a room used for dentistry, has been put aside for six children, mostly clueless, certainly helpless, and they sit there opening their presents. A Rubik's Cube here, a Teddy Ruxpin there - Christmas has literally come early as we're only in the first week of November 1980.

The six kids sit looking at each other in misplaced wonder, tripping over the endless gifts handed over by nurses and doctors, all of these professionals hoping that the presents will help solve a problem their medical talents cannot. Tugs-of-war over unopened packages break out left, right and centre as the excited children try and forget what is happening, what is at stake.

If only these children really knew. This is to be the last 'Christmas' their mother will spend with them and those wee children will remember little else apart from wading through the mounds of wrapping paper on the floor while looking up at the tear-filled eyes of those medical staff popping in and out, hoping to help, hoping for a miracle, as the children detect the catch in the throat of the ward matron, desperately trying to say something positive, something cheerful.

This shouldn't be happening.

Not to that grand-looking woman of 41, lying in a bed in a Manorhamilton hospital, slap-bang on the N16 in County Leitrim, surrounded by machines beeping, lines feeding, drugs seeping. Yet it is.

Agnes Given, she of the jet-black hair, falling across her emaciated shoulders, has 12 weeks to live.

Agnes Given, a mother of six, the eldest 11, the youngest two.

Agnes Given, my mum, dying, me aged four.

Agnes Given, a woman I can barely remember, a mother I will never forget.