As any pub quiz regular will tell you, the Hawthorns, home of West Bromwich Albion since 1900, is the highest league football stadium above sea level in the UK. It stands 551ft up on a ridge west of Birmingham and all last week it was a place of pilgrimage, a city on a hill. From the moment fans heard of the death of Cyrille Regis, at 59, last Sunday, they trooped up here in ones and twos, in sleet and rain, to tie scarves and shirts to the ground’s blue-painted iron gates.

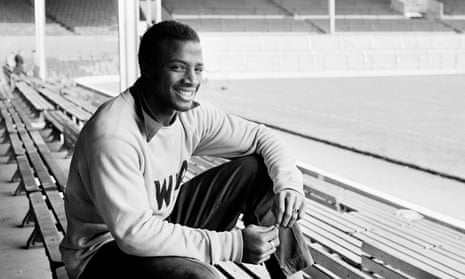

Empty football stadiums always carry the ghost of Saturdays past; you half hear the roar they are built to contain. That roar was never louder here than 40 years ago when Regis led the forward line alongside his best mate Laurie Cunningham. The eyes of those who have come to pay their respects shine with the memory of it when I ask. First they talk of Regis’s power: “He was so strong, and so quick”; “There was no stopping him, once he got into his stride.” And then they talk of his grace: “He was just such a lovely bloke, a proper gentleman.”

On Thursday lunchtime Graham Chambers was sticking a handwritten note to the gates. The note recalled a full-throated hymn of 1978:

Hark now hear the West Brom sing!

A new king born today!

His name is Cyrille Regis

And he’s better than Andy Gray!

I tell him I last heard that song as a 12-year-old Aston Villa fan, from the rival end of the ground; Andy Gray was our player. He smiles. “Cyrille was born exactly the same day as me,” he says. “I told him that a couple of times but we never worked out who was older.”

Much of the talk last week was of Regis’s impact as the first black hero of the English game, slowly changing attitudes; but up here they just loved him from day one. “The first game he played, he scored two goals, the second just bang in the top corner,” Chambers says. “We all just looked at each other: ‘Where’s he come from?’”

The answer to that is another reason why Regis’s death was so poignant. His story, like that of all genuine heroes, was one of struggle. His first five years were spent in a rainforest village without a school, a boat ride upriver from the capital of French Guiana, Cayenne. His dad dug desperately for gold, and when he found none, aged 46, he headed for England. Regis followed in the hard London winter of 1963 with his mother and sister, not knowing what cold was. The four of them lived in a single room at 383 Portobello Road, Rachman territory. Then, when things got worse, Regis and a younger brother were taken in by a convent while their mother lived in a Salvation Army hostel. Eventually they were reunited in a high rise adjacent to Wembley stadium.

Though Regis, a trained electrician, was a standout non-league footballer, he was rejected by the big London clubs. The Albion scout Ronnie Allen was so sure of his ability he offered to pay the 19-year-old’s wages – £60 a week – himself.

A quarter of that went on the digs that a part-time coach arranged after asking at the factory in Dudley where he worked if anyone knew a black landlady to take the player in. Murtella Groce, who became a lifelong friend to Regis – he visited her often after she developed Alzheimer’s in her 90s – gave him a room in her terraced house in Smethwick. Her home was in the constituency where a decade earlier the Conservative candidate, Peter Griffiths, had won an election with posters stating, “If you want a nigger for a neighbour – vote Labour”.

For that first Albion match in 1977, Regis walked the half an hour from Groce’s, across the canal, past Handsworth cemetery to the Hawthorns with his boots in a bag on his shoulder. It was probably the last time in West Bromwich he went about unrecognised.

The racism from opposition fans never stopped shocking him, but he had a ready answer. The first time the monkey noises rolled down from the terraces was in a game at Newcastle. He and Cunningham both scored. When Regis was in the England dressing room before his international debut he opened a letter which read: “If you put your foot on our Wembley turf you’ll get one of these through your knees.” Also in the envelope was a bullet. He kept the bullet, and went on to play five times for England.

He knew it should have been more. And there were other might-have-beens after those first three explosive seasons. St Etienne wanted to take Regis to France for £750,000. Johan Cruyff wanted him at Ajax, to replace the world’s best centre forward, Marco van Basten. At the time of the first offer he was persuaded to stay at West Brom for £200 a week and a one-off £11,000 loyalty bonus. As a couple of the West Brom fans at the gates tell me, ruefully: “We now have defensive midfield players who can’t get a game on 70 grand a week.” That’s the other reason that Regis’s death has resonated; he was of the last generation of football heroes who was, in other respects, also one of us.

On the way home from the Hawthorns on Thursday, I heard a radio report that suggested this weekend’s fixtures would mark how Regis “had led the fight against racism”. This sounded slightly wrong-headed. Regis never stooped to engage directly with the bigots. He just showed Saturday after Saturday, year after year, in the way he played his football and carried himself as a man, the emptiness and absurdity of those who abused him. As he said in his autobiography: “Through this reply of consistent perseverance and performance, people’s minds were changed.” Football came first – thrilling, unforgettable for those who watched him: all the rest followed.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion